Politics of Kant’s Universalism

My doctoral thesis, Kant’s Universalism in Historical Context: Repoliticising the Foundations of a Seminal Political Philosophy (2024) successfully underwent an oral examination, receiving recommendations for refinement to facilitate its transformation into multiple publications. The original contribution of my thesis is twofold.

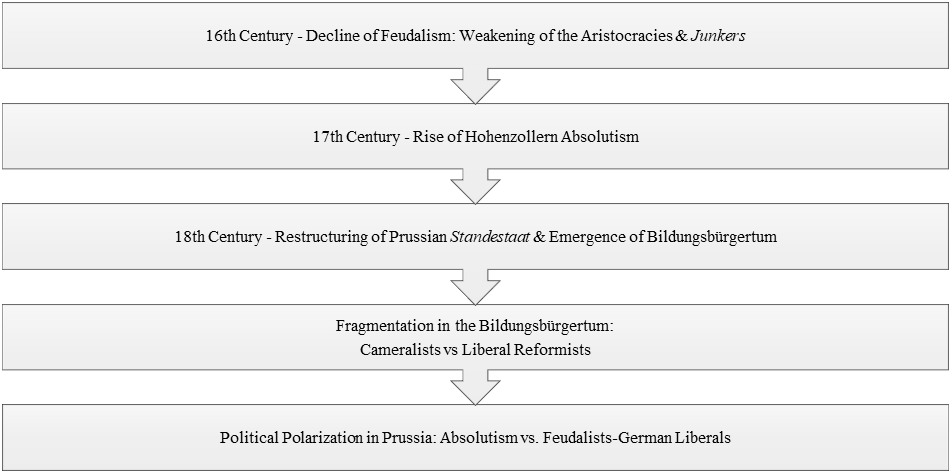

Firstly, I conducted a meticulous historical exploration of the emergence of distinct social classes during the Prussian state-building process. I delved into their responses to the extended decline of the traditional feudal system in German-speaking Europe, revealing intricate connections between political ideologies and proposals. Responses to the prolonged feudal crisis in the German context were categorized into traditional feudal, absolutist paternalist, and liberal reformist, each originating from different class positions and offering unique political projects to address the crisis’s impacts.

This investigation illuminated the Bildungsbürgertum, the educated professional bureaucratic faction within the Bürgertum, as a distinct and independent social class. Applying Marxist terms, I identified this class as directly controlling social property relations within the state apparatus, functioning as an apparatus for appropriating revenue from producer classes.

Following this identification, I positioned Immanuel Kant as a member of the Bildungsbürgertum, particularly during his academic career, contextualizing Kant’s universalist political thought within the class politics of the Bildungsbürgertum. Kant’s philosophical propositions evolved as responsive solutions to key issues in the German/Prussian context, transcending previously canonized particularistic endeavours by absolutist-paternalist, traditional feudal, and liberal reformist traditions.

The research findings and contributions have been emphasized in academic commentary. Acknowledging the comprehensive nature of my discoveries, I contend that a single academic document cannot adequately encapsulate all aspects, necessitating the delineation of at least two article-sized products. Accordingly, the historical investigation forms the primary focus of my first article project, while the repoliticisation of Kant’s universalist political philosophy emerges as a secondary complementary endeavor.

Research Topic

The primary objective of the original doctoral dissertation was to scrutinize Immanuel Kant’s relationship with the historical context of his era, specifically the protracted political and social crisis prevalent during his time. The research aimed to elucidate the historical and social influences that shaped Kant’s propositions concerning the establishment of a political order grounded in universally applicable principles. By delving into the historical and social milieu, the study brought to light the contours of Kant’s universalism while underscoring the inherent limitations of his visions. The overarching goal was to elucidate the constraints of Kant’s political universalism, connecting these limitations to his endeavor to reform the context by advancing his class, the Bildungsbürgertum. Therefore, a fundamental assumption of this thesis posited that Kant’s political universalism was circumscribed by the material and social backdrop associated with the thinker’s class.

In contrast to classical Marxist readings that primarily aligned thinkers with their class positions, portraying them as political operatives and propagandists, this study departed from such simplistic categorizations. Instead, it subjected Kant to scrutiny within the historical context of Prussia and employed a materialist perspective to analyse him in the framework of a structural crisis.

Concurrently, the dissertation posited that understanding Kant’s relationship with the Bildungsbürgertum, his own class, necessitated consideration of the enduring impacts of the crisis of feudalism on German political and social thought. Employing the methodology of the social history of political theory, the research investigated responses to pivotal questions in politics and philosophy that evolved amidst the protracted crisis of feudalism.

The planned outcome of this research entails two sequential publications. The first publication will delineate the historically specific characteristics of the German context, particularly in relation to the extended decline of feudalism, and define the Bildungsbürgertum as an authentic social class. In the second publication, the focus will shift to an examination of the key questions plaguing the political philosophical landscape of German-speaking Europe, juxtaposed with Immanuel Kant’s universalist political philosophy.

Research Questions

The relevant research questions appear here as:

- What are the profound implications of the feudal downturn in Europe, commencing in the 15th century and extending into the German context? How can the identification of social property relations during this period contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the societal changes that transpired?

- What were the primary responses to the prolonged feudal downturn from the significant components of social property relations? In what ways did these responses lead to the political constitution of property, and how did this interplay contribute to the broader socio-political transformations during this historical period?

- What kind of political project does Kant’s universalism propose in terms of political polarisations between Absolutist-paternalism, Traditional Feudalism, Liberal Reformism in the Prussian context?

- How can Kant’s universalist philosophy be repoliticized through the social and material grounds that formed Kant’s historical context?

Primary Purpose & Main Assumptions

In competition, the primary purpose of this research was to show that Kant’s universalist political philosophy could be reconsidered using the social history of political theory method by reviewing Kant’s relationship with:

(i) impacts of the prolonged crisis of feudalism to the political and legal philosophy

(ii) Prussia, where the Enlightenment (Aufklärung) flourished under an absolutist state-building process

(iii) and with the ideology/reform project of the Bildungsbürgertum of the rising educated bureaucratic classes who became more influential in the control of social property relations.

Potential Outcomes

The research unfolds four pivotal key findings, each offering unique insights into the intricate dynamics of Immanuel Kant’s political philosophy within the historical context of the protracted crisis of German feudalism. Firstly, the examination of the impacts of the long crisis revealed three interconnected responses, emanating from distinct social classes engaged in conflicts over social property relations. These responses not only characterize the social property relations but also delineate how politically constituted property assumes historical specificity in the German/Prussian context. The second key finding pertains to the Bildungsbürgertum, presenting Kant as an exponent of this social class. Departing from conventional classifications, this research redefines the Bildungsbürgertum as a social class, transcending its prior characterization as a mere stratum or intellectual elite. Kant’s distinctive epistemological framework, rooted in universal conditions, emerges as a central discovery, forming the bedrock of his political theory.

The third key finding is the revelation that Kant’s political universalism is intricately linked to his understanding of the Bildungsbürgertum. Beyond its theoretical originality, Kant’s universalist political philosophy addresses practical concerns, aiming to consolidate the Bildungsbürgertum under the Aufklärung and establish a universalist political order devoid of a revolutionary agenda. Moreover, to resolve internal polarization within the Bildungsbürgertum, Kant devises a unique universalist approach, promoting principles that engage every actor actively.

In terms of contributions, the research pioneers a historical materialist analysis of Kant’s political universalism using the social history of political theory method. This marks a groundbreaking exploration, as it situates Kantian scholarship within the context of the long crisis of feudalism in Germany, offering a novel perspective on his political theories. The second contribution lies in defining Kant as an intellectual of the Bildungsbürgertum, presenting this class as a social entity rather than a mere stratum or intelligentsia. Beyond intellectual and philosophical outputs, the research delves into the material class interests internalized by the Bildungsbürgertum within the Prussian Ständestaat. The third contribution involves a historical materialist exploration of Kant’s epistemological break, linking his method to a purpose of presenting a social epistemology defined in the public sphere. The fourth and final contribution scrutinizes Kant’s political universalism, contextualizing it within the debates surrounding the French Revolution and unravelling the class limits of his universalism, shedding light on the restrictive elements of Kantian thought. Collectively, these findings and contributions illuminate Kant’s political philosophy in a nuanced and historically grounded manner.

Berkay Koçak, PhD

Political Scientist & Policy Analyst